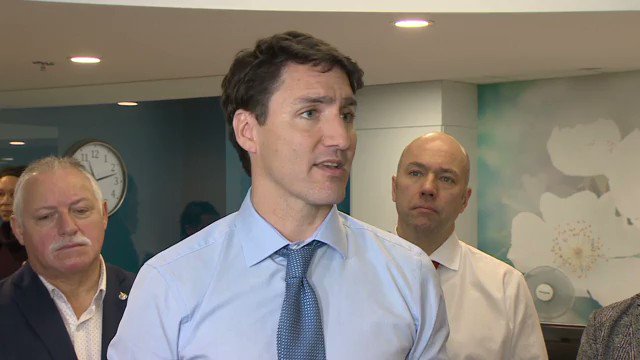

"Unthinkable." That's how Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reacted when Quebec tabled a law that would ban religious symbols and clothing for its teachers, judges, police officers and other public sector workers.

He pledged to "defend the rights of Canadians" against the proposed ban. His minister of justice repeatedly called the bill "unacceptable" and alluded to "next steps" once it became law.

"Unthinkable": Justin Trudeau, Andrew Scheer and Jagmeet Singh condemn Quebec's secularism bill, which, among other measures, would ban many public workers from wearing religious garb or symbols#cdnpoli

161 people are talking about this

One should not doubt Trudeau's inherent repulsion for the Quebec law and everything it embodies. This is the man who heralded a woman's right to wear a niqab — the starkest symbol of oppression of women — to a citizenship ceremony at which she would pledge to adhere to a Constitution that specifically defends gender equality.

Trudeau the father only paid lip service to multiculturalism and the veneration of differences. Trudeau the son embodies it in his bones. It is certain that, if re-elected, he will act. How? More on this later.

But the bill became law in late June, and no action has been taken since. On the contrary, the Liberal government has evaded and procrastinated on the issue. Why?

There is an inconvenient bump on the road to squashing the Quebec law: public opinion. Quebec public opinion, certainly, but Canadian public opinion also. It can — and will — no doubt be disregarded the morning after the election, but not the mornings before.

Ban has support outside Quebec

In April, Léger Marketing carried out a country-wide online poll asking if voters would support the ban of religious symbols for teachers, police officers and judges in their province. The poll also asked respondents who they would vote for in the federal election.

Outside Quebec, fully 40 per cent of Canadians approved of such a ban in their own province. Except in Alberta, 50 per cent or more of Conservative voters were in favour.

Case closed.

Problem is, a sizable chunk of Liberal voters also embraced the ban. Here are the numbers: Atlantic Canada, 28 per cent; Alberta, 31 per cent; Ontario, 32 per cent; B.C., 34 per cent; Prairies (Manitoba and Saskatchewan), 62 per cent. (Would you believe that the numbers are even higher for NDP voters!)

Liberal pollsters have seen these or similar numbers. And they know that 50 per cent of their Quebec voters support the ban, according to the Léger poll. Were they to make this one of the pivotal issues of the campaign, they would have to turn their backs on a third of their base — and give up any chance of forming a majority.

Tough luck.

An election is precisely the moment when truths must be told.

If Trudeau really thinks the ban is "unthinkable," and I'm sure he does, he must tell voters exactly what he plans to do about it if re-elected.

Trudeau should reveal what he plans to do about the ban

Three options are available to him. The most extreme, let's call it the nuclear option, is to use the old disallowance clause of the Constitution to simply squash the legislation. This option, promoted by pundits such as columnist Andrew Coyne, was last used in 1943 against an Alberta law that restricted the property rights of Hutterite colonies.

There is a deadline on that option: it can only be used within 12 months of the law being sanctioned by the governor general, thus, no later than late June 2020.

The mid-range option is to refer the question of whether or not the law is constitutional directly to the Supreme Court. Constitutional scholars meeting in Toronto last April concluded that recent jurisprudence would lead the court to declare the law invalid — on its merits and despite the use of the notwithstanding clause. They said the court could also severely curtail the use of the notwithstanding clause itself and declare that Quebec really had no right to use it pre-emptively.

The milder option would be for Ottawa to join the ongoing legal challenge of the ban by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association and National Council of Canadian Muslims and help bring it before the Supreme Court.

Are any of these options off the table for Trudeau? The election campaign should not end without a clear answer to that question.

Look to Europe, not Ottawa

Those who think Canadian multiculturalism is the only possible answer to the challenges of diverse societies will keep pushing hard against the ban. As did CBC's Robyn Urback, who wrote recently that the Quebec law was a "national disgrace," nothing short of "state-sponsored, systemic oppression" and called on Trudeau to denounce it as he had other "policy wrongs of the past," such as the hanging of First Nations chiefs in the 19th century.

Proponents of this point of view are also present in the NDP — and to a lesser extent in the Conservative Party — and will want to know why their leaders seem indifferent in the face of Quebec's perceived assault on equality rights.

Quebecers, on the other hand, know that the cradle of rights and freedoms is not in Ottawa but Europe. And that European courts have ruled that states have legitimate grounds to demand a clear separation of Church and state — including when it comes to the attire of civil servants — and to promote the rights of women by prohibiting misogynist religious garb.

So the question is, really, about tolerance. Will the Liberals and other federal parties tolerate the existence within Canada of a nation that disagrees with their brand of multiculturalism?

Trudeau claims he accepts the existence of Quebec as a nation within Canada. Will he say that doesn't mean a thing when that nation veers from the Canadian norm?

He knows that no Quebec government to date has signed the current Constitution, and each one has rejected multiculturalism as a policy. Will he nonetheless use this unsigned Constitution as a hammer against a very popular Quebec law?

The Quebec government of François Legault played by the rules when it passed the law in June by invoking the notwithstanding clause to forestall any potential charter challenge. Will Ottawa now ask the Supreme Court to change the rules once the game is already underway?

Quebecers want to know; Canadians, too.