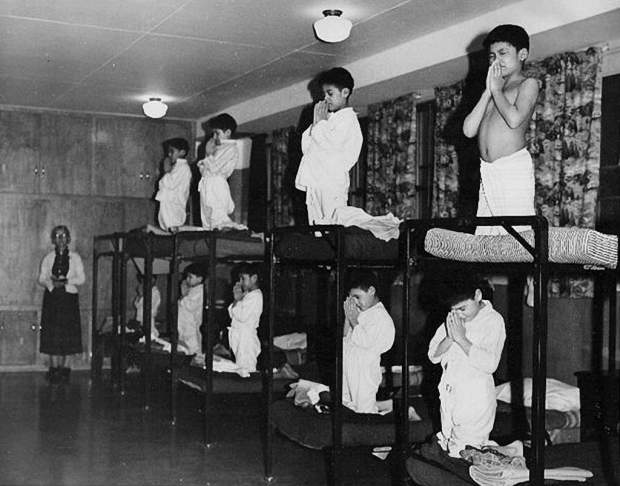

The “cultural genocide” of Canada’s indigenous people in residential schools is more of a “mourning metaphor” than an accurate legal label, more a “song of bereavement” than a specific indictment under international laws.

That is the controversial argument put forth in a lecture Thursday night by Payam Akhavan, professor of law at McGill University, former United Nations war crimes prosecutor, and now one of the most prominent public figures to question — however tentatively — whether Canada was ever a truly genocidal colonial power.

He does acknowledge there is a way to read the 1948 Genocide Convention’s ban on “forced transfer of children” as supporting a claim of biological genocide — the elimination of an entire generation, preventing a group’s procreation — provided the specific genocidal intent was in place. A similar argument can be made about forced sterilizations.

But “cultural genocide” is a different claim, he said, and the current fixation on the term threatens to leave Canadians “lost in abstractions,” and unable to “fathom the depth of human suffering.”

His main point is that residential schools were so clearly a crime against humanity — persecution — that he is somewhat baffled by the “insistence” on using the far more debatable term “cultural genocide,” with all the historical and legal baggage it carries.

“The question is whether ‘cultural genocide’ has a legal meaning, and if not, why these words are vested with so much power,” he told an audience at York University’s Glendon College in Toronto, before surveying the various international legal precedents that inform the question, none conclusively.

Some people will surely be annoyed by his analysis, he said earlier, over a traditional Persian lunch of chicken and beef over rice and spiced yogurt in a Toronto restaurant that displayed a replica of one of the earliest human rights codes, the Cyrus Cylinder.

Akhavan, whose thoughts on human rights as they relate to suffering and redemption will form the basis of an upcoming series of the popular Massey Lectures, is especially well-placed to criticize Canada’s new view of itself as a genocidal power. A member of the minority Baha’i faith, he fled Iran with his family as a young boy, grew up in Toronto, studied law first at Osgoode, then at Harvard Law School as a classmate of Barack Obama, whom he remembers as a “radical skinny kid with a backpack.”

As a United Nations prosecutor for war crimes in Yugoslavia, where he was targeted for assassination, he remembers thinking of the genocide question, “Who cares?”. Academic and legal distinctions seemed to wither in the presence of mass graves and systematic rape. Later, after similar work in Rwanda and elsewhere, terminological debates seemed to him to reflect the “professionalization of human suffering.” Survivors have stories, he realized, which are more important than the labels we put on them.

“I felt there was a human rights industry that was so detached from the reality of suffering,” he said. “Everybody says the right things, but somehow nothing changes.”

Though it has been current in academic and indigenous circles for years, and was even used by former prime minister Paul Martin, the idea of “cultural genocide” against indigenous people entered Canadian popular discourse last year with a bang, first when it was used in a speech by the Chief Justice of Canada, Beverley McLachlin, and then a few days later, when chairman Murray Sinclair made it a cornerstone of the report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Akhavan recalled the applause that greeted Sinclair’s use of the term, describing it as a “moment of rhetorical redemption for the long-suffering survivors.”

Pitched argument followed, between those who saw the term as a rightful recognition of Canada’s genocidal colonial shame, and others who saw it as an exaggeration, wrongly equating residential schools with the seminal atrocity of the Holocaust and the deliberately bloody horrors of Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

Akhavan notes that the Canadian Museum for Human Rights refused to use the term “genocide” for Canada’s crimes against indigenous people, and indeed when it opened, there were First Nations protests outside. That decision followed the government’s official recognition of just five genocides: Rwanda, Srebrenica, Armenia, the Holodomor and the Holocaust.

We reduce the enormity of human suffering to the rationalist credo of academic concepts in self-delusional rituals that make lofty incantations a substitute for meaningful action.

McLachlin’s use of the term gave rise to concerns that this issue might end up before her court, possibly even before her retirement in 2018. But with no criminal prosecutions likely, and many civil claims of survivors settled in broader agreements, this seems increasingly unlikely. And even if it does, Akhavan observes, the difference between the crime against humanity of persecution and the crime of genocide means little to civil law, both being equally culpable and heinous.

More important is the fair and accurate retelling of history, the empathetic treatment of survivors and the national project of reconciliation.

Cultural genocide does, in fact, have a legal meaning. The trouble for Canadians is that this legal meaning was specifically excluded from the 1948 Genocide Convention, partly because of Canada’s objection to it, on the grounds that it was “intended to cover certain historical incidents in Europe that have little essential relevance in Canada,” as the government of the day put it. This exclusion means “cultural genocide” today is like the ghost of a crime.

Akhavan knows denying Canada’s genocide is a risky project. Survivors might resent this apparent minimization of their plight, but he understands the power of “misplaced and displaced anger,” even against scholars who have made it their life’s work to redress genocidal injustice. Academics and indigenous leaders might resent his criticism of a fundamental concept in decolonization theory, but his argument is solid, legalistic, cautious and respectful, revealing the quirks of history that led to the definition of genocide, and the exclusion of cultural genocide.

Key to this process was the horror of the Holocaust, which set a bar so high few countries have come close to matching it. On the other hand, its legal designation as the ultimate crime of genocide made it possible for other victims and survivors to appropriate its legacy, and elevate their demands for justice to a similar status.

“Yet, in the killing fields of Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur, and today, in Iraq and Syria, we witness what are often sterile polemical debates on the genocide label, a pretense of empathy, creating the illusion of progress, while we remain bystanders to radical evil. We reduce the enormity of human suffering to the rationalist credo of academic concepts in self-delusional rituals that make lofty incantations a substitute for meaningful action,” Akhavan said.

“I think on the one hand it’s understandable that some of the delegates (to the 1948 convention) believed that the physical extermination of people in gas chambers has to be seen as a different idea than the destruction of monuments or the burning of books and those kind of acts we associate with cultural genocide. But on the other hand, in 1948, the majority of the countries that are now members of the United Nations were still overseas colonies of the European powers. Had they been involved in negotiating the Genocide Convention, they would probably have brought their own experiences and priorities to the table and we may have ended up with a different definition of genocide. Now that did not happen, but it’s important to bear in mind that for people who have been subject to colonial domination, maintaining their identity is as important as physical survival.”

‘Cultural genocide’ of Canada’s indigenous peoples is a ‘mourning label,’ former war crimes prosecutor says

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé