A recent study from Cornell University finds a probable link between drilling activity and an increased frequency of earthquakes in Oklahoma. Published in the journal Science, the study indicates that the practice of injecting millions of gallons of wastewater underground after a well is hydraulically fractured may increase the occurrence of earthquakes.

Although scientists have yet to identify a concrete link between unconventional drilling and earthquakes, areas that have experienced an increase in oil and gas drilling have also seen an uptick in seismic activity. Oklahoma is currently the state with the highest number of magnitude 3.0 earthquakes for 2014.

“It's been a real puzzle how low seismic activity level can suddenly explode to make (Oklahoma) more active than California,” says Katie Keranan, the lead researcher of the study and geophysics professor at Cornell University.

A correlation between earthquakes and drilling have cropped up elsewhere, including Ohio, where regulators shut down several wells that were thought to have contributed directly to earthquakes.

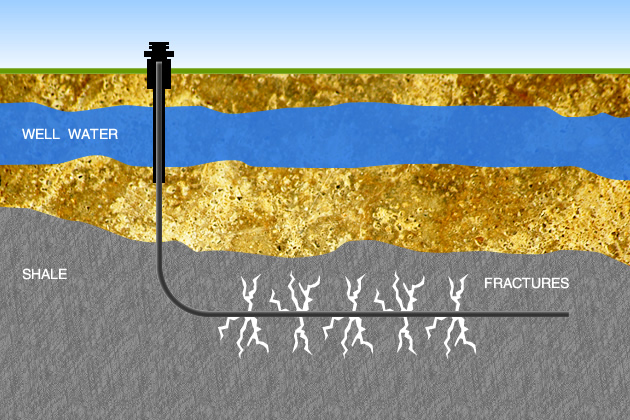

As in previous cases, the latest Cornell study finds more culpability with injection wells rather than the fracking process itself. After a well is fractured, millions of gallons of wastewater flow back up the well.

Operators dispose of that wastewater by sending it to injection wells – the water is injected

underground in between impermeable layers of rock for long-term storage.

Ohio, in particular, has a large concentration of injection wells, and much of the wastewater from the thousands of fracked wells in places like West Virginia and Pennsylvania is trucked to Ohio for disposal. The injection wells are thought to be a contributor to earthquakes.

However, the Cornell study still does not find a conclusive and definitive link between injection wells and earthquake activity, a fact that the oil and gas industry was quick to point out. In any case, industry allies argue, places like Oklahoma and Ohio may have seen an increase in earthquake activity, but the relatively few instances pale in comparison to the thousands of injection wells used. For example, only four injection wells have been linked to earthquake activity, out of a total of 4,500 that have been drilled in Oklahoma.

Mike Terry, President of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association (OIPA), doubts the veracity of the connection with earthquakes, and argues that wastewater disposal is not new to Oklahoma.

“Disposal wells have been used in Oklahoma for more than half a century and have met and even exceeded current disposal volumes during that time. Because crude oil and natural gas is produced in 70 of Oklahoma’s 77 counties, any seismic activity within the state is likely to occur near oil and natural gas activity,” he said in a response to the Cornell study.

But although the report stops short of declaring a clear link between injection wells and earthquakes, the findings add to the growing body of evidence establishing that link. The research found that when migrating fluids run into fault lines, pressure can build up and contribute to the rupturing of a “critically stressed” fault line.

Cornell’s Katie Keranan says the results suggest that more monitoring is needed. “Earthquake and subsurface pressure monitoring should be routinely conducted in regions of wastewater disposal and all data from those should be publicly accessible,” Katie Keranan said. “This should also include detailed monitoring and reporting of pumping volumes and pressures.”

Predictably, the oil and gas industry is warning against any hasty moves to crack down on drillers. Mike Terry of OIPA cautioned against “a rush to judgment based on one researcher’s findings.”

That is because if the facts prove to be as damning as the research suggests, the industry could face stiffer regulations, which will increase costs, or in the worst case, curtail drilling activity.

In Ohio, regulators implemented several strict conditions to new permits, including requiring the installation of sensitive seismic monitoring equipment for all wells within three miles of a known fault line. Also, if a magnitude 1.0 earthquake occurs, drilling will be suspended while safety officials evaluate the area, and permanently halted if a link is found.

Oklahoma regulators have yet to apply such scrutiny. But the latest study will increase the pressure to do so.

New Research Strengthens Link Between Shale Drilling And Earthquakes

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé