Andrew Coyne says Donald Trump is “not a rational actor.” He’s recently said as much twice, in fact, in two separate National Post columns. Is Trump rational? It depends on what the meaning of the word “rational” is.

The heavy hits Trump has taken this week, first from Bob Woodward’s new book and then from the anonymous New York Times op-ed by “a senior official in the Trump administration” (who for the Times’ sake had better not be some assistant deputy secretary of this or that) underscore Trumpian character flaws long apparent to anyone even half paying attention.

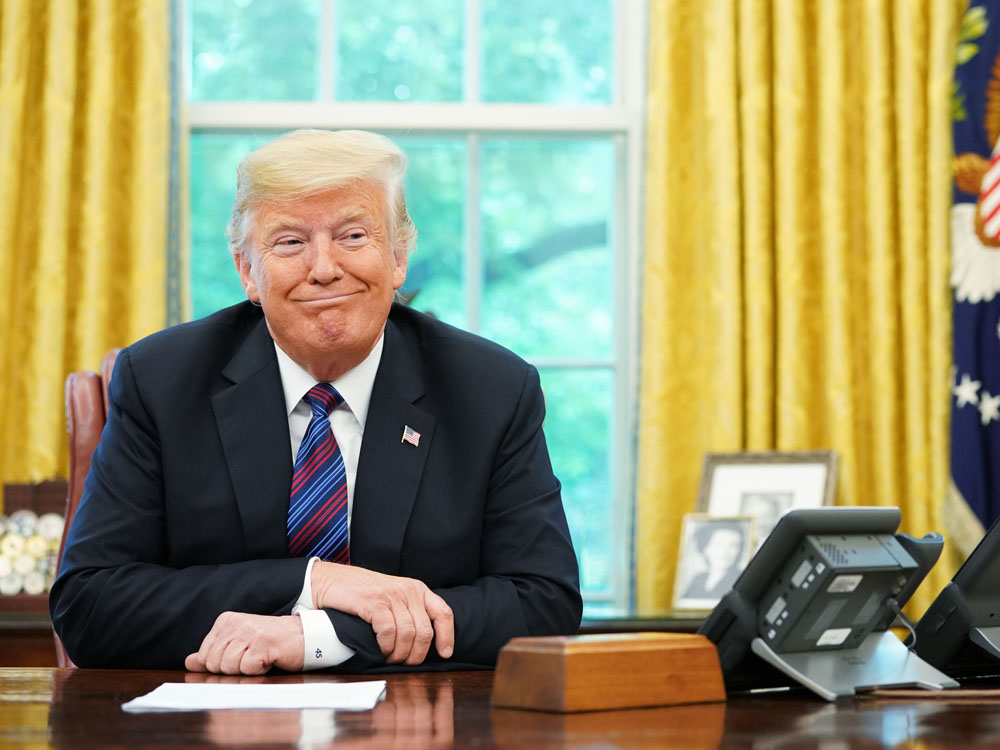

There’s no doubt Trump is a repellent actor. He embodies all the worst traits of contemporary culture. He’s flighty, shallow, self-absorbed, brash, vulgar, oversexed, incurious, inattentive, unreflective — none of which is surprising from someone who made his name in TV and reportedly watches it five to six hours a day even while holding down the most important job in the world. To the extent Trump is made in the image of the culture we have all created, we only have ourselves to blame.

He’s also, in many instances, a completely unreasonable actor, in terms of goals. But is he an irrational actor? The Goldwater Rule of the American Psychiatric Association prohibits analysts from providing a professional opinion of people they have not personally examined. And of course any clinicians who may have attended to Mr. Trump can’t comment because of doctor-patient confidentiality — unless he waives that, which he presumably would do only if said clinician judged him “the sanest person ever elected to the presidency,” to paraphrase the 2015 assessment of his physical health by his personal physician.

Does the president understand right from wrong, as he would have to do to stand trial in many countries’ courts? Good question. On lots of issues — separating illegal immigrants’ kids from their parents, for instance — he has trouble making what would seem to be no-brainer moral choices. Many accounts of his business dealings suggest he has only one maximand: his own bottom line.

Trump has got this country over a barrel, which apparently is where he wants us

Is he rational in the sense of understanding how to get from status quo “A” to desired outcome “B”? One big example suggests he is: the current NAFTA negotiations. Any reasonable assessment of the state of the negotiations is that Trump has got this country over a barrel, which apparently is where he wants us, and the barrel is racing toward the falls.

Is it reasonable that he wants Canada over a barrel? Not if alliances mean anything. At literally the 11th hour in October 1987, Brian Mulroney appealed to Ronald Reagan’s sense of friendship: “Ron, I want you to explain to me how it is that you have just concluded, the Americans have just concluded, a nuclear reduction treaty with their worst enemies, the Soviet Union, and you can’t conclude a free trade agreement with your best friends, the Canadians.” In the end, Reagan preferred not to have the deal fail and we got the dispute-settlement mechanism that’s currently at issue.

But now we’re faced with a president who: is contemptuous of our prime minister, sets little store by our two countries’ long alliance, listens to a negotiating team that resented being preached to about feminism and human rights, and wants to re-jig the pattern of advantage in NAFTA. Many people, myself included, think those goals are unreasonable. But has Trump been irrational in his pursuit of them? He started by offering us a separate deal, which we rejected. He then went for divide and conquer with the Mexicans. Now we’re over the aforementioned barrel, hoping that just before a mid-term U.S. election a heretofore supine Republican congressional majority will rescue us when the president goes to them with Canada’s amputation from NAFTA.

As an example of presidential reasonableness with some problems in A-to-B rationality, consider — don’t laugh! (yet) — Russia. In the 1970s, two of the heaviest-weight U.S. geopolitical strategists, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, opened relations with China so as to blunt the influence of their main rival at the time, the Soviet Union, which seemed to have stolen a historical march on a West deep into its pre-Reagan “malaise.”

Who’s the rising rival to America now? China. What’s the smart strategic thing to do? Get closer to Russia. Granted, the current tsar is an unsympathetic sort with his own distasteful ambitions. But there’s a certain amount of reasonableness to such an approach.

That Trump comes to this view instinctively rather than intellectually, that his personal diplomacy is bumbling and naïve, that other U.S. actors are ramping up hostility to Russia that Trump would like to dampen, merely cloud the strategic arguments.

Repellent? Almost always. Reasonable? Many times not. Rational? Given his goals, surprisingly often.