The year was 1878, and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald had a plan, a glorious plan to build a country that was “allied together,” more than just a collection of provinces.

He was going to do it via a three-part strategy of immigration, building a railway to British Columbia and a system of tariffs to protect central Canadian business from the depredations of American competitors, creating an east-west system of trade in Canada.

The first two formed a foundational part of Canadian identity. The third sparked a resentment for eastern Canada that’s been smouldering ever since.

“I believe that, by a fair readjustment of the tariff, we can increase the various industries which we can interchange one with another, and make this union a union in interest, a union in trade, and a union in feeling,” Macdonald proclaimed.

These words were the seeds that sprouted what we’d now call western alienation, populism, separatism, in all its incarnations. History, at least when it comes to anger in the west, is repeating itself — has been repeating itself — for well over a century.

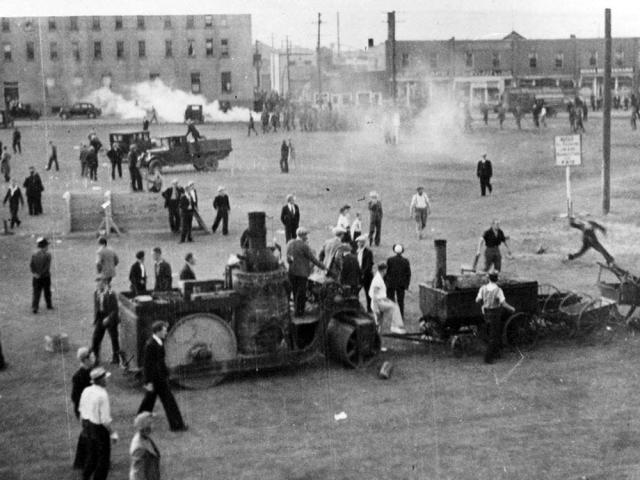

From Louis Riel walking the steps to the gallows in 1885 in Regina, denunciatory editorial cartoons in the early 20th century, the Trek to Ottawa during the Great Depression, right on through to the Republic of Western Canada ballcaps during Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Program, then on to the creation of the Reform party and I (heart) Canadian Oil and Gas T-shirts in the legislature and denunciatory Facebook memes, this defining issue of the latter half of 2019 has its origins more than a century ago.

“It’s almost always been economic, economic, economic,” says Preston Manning, the former head of the Reform party, in a recent interview. “The fact that this is a periodic thing, I think indicates that (there are) some fundamental problems in the way that federation itself is structured.”

***

In the immediate aftermath of the 2019 federal election, it feels like western alienation is at an all-time high, with significant risks for national unity. In June, several premiers — most of them conservative, and some of whom may even benefit politically from the anger — wrote to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about resource-related legislation, saying it put national unity in danger.

Trudeau hit back, saying it was “irresponsible” of the premiers to bring it up. Still, after his election in October, he addressed it more broadly: “It’s extremely important that the government works for all Canadians, as I’ve endeavoured to do over the past years and as I will do even more now, deliberately.”

It’s almost always been economic, economic, economic

Anywhere you look — at any point in our history — you see and feel incarnations of alienation.

Take 1997, when British Columbians were feuding with the federal government about the salmon fishery, and Sen. Pat Carney suggested separation might be a bargaining tactic for B.C. Stéphane Dion, then the Liberal government’s “unity minister” wondered, “goddamn, what does this have to do with the secession?”

To which Glen Clark, the premier, had an answer: “Salmon has everything to do with national unity because it’s a symbol of Ottawa’s failure to recognize the unique issues that concern British Columbians.”

That may sound familiar to anyone who’s listened to Jason Kenney recently.

Roger Gibbins, a senior fellow at the Canada West Foundation, and an authority on alienation, said it’s “a frustrated sense of Canadian nationalism.”

“There’s a frustration that the region has been unable to play a significant role in the evolution of the country,” Gibbins says.

Angus Reid Institute polling from last winter indicated 50 per cent of Albertans believed separation was a real possibility and 60 per cent would either strongly or moderately support the province joining a Western separatist movement.

After the election, Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe warned the way the ballots had been cast in the west was indicative of a distinct level of discontent. Out of Alberta’s 34 seats in Parliament, 33 went to Tories; in Saskatchewan, all 14 seats went to Andrew Scheer’s party.

“Last night’s election results showed the sense of frustration and alienation in Saskatchewan is now greater than it has been at any point in my lifetime,” wrote Moe in a letter Justin Trudeau.

***

The way the votes were cast in 2019 isn’t an enormous aberration. In 2015, when Albertans sent four Liberals and one New Democrat to Ottawa, that was the odd one out. Melanee Thomas, a University of Calgary political scientist, points to 2006, when Stephen Harper swept the province.

“This voting pattern is not new,” says Thomas.

Albertans — and in large part, those in Saskatchewan — have long elected conservatives of various stripes, whether from the Reform party, the Canadian Alliance or Conservative party federally, or Wild Rose, Progressive Conservatives, United Conservatives or Social Credit, provincially.

But Albertans also have a history of protest votes, sending alienated westerners through the early- to mid-20th century to represent them in Ottawa. It’s manifested, perhaps, in other ways, too: All of the Famous Five, who fought for women’s suffrage, were Albertans.

At various moments, alienated Albertans have been considered, to some extent, a nascent threat to confederation.

Until 1984, the RCMP kept a weather eye on western separatists, among them, Elmer Knutson, who founded an Edmonton car dealership, the Confederation of Regions Party and declaimed against Liberals “who want the state to be the ‘sugar daddy,’” in his self-published pro-western-independence treatise A Confederation or Western Independence.

“The prime overriding issue is that (separatists) see western interests being dominated and eroded by all sorts of ‘Quebec’, ‘Ontario’ and/or ‘Eastern’ business and government power brokers, and they feel they are in a box, with the only escape route to vent these feelings is to separate,” said a 1980 RCMP memo.

Knutson, while a noted crank — he claimed Manning stole all his popular ideas for the Reform party — traced his grievances back more than a century, and wrote Canada was premised upon the “myth of confederation.”

“The names of our earlier defenders echo across time like battle cries: Riel, Poundmaker, CCF, United Farmers and more,” Knutson wrote.

On that front, there’s some truth to Knutson’s words.

***

In his 1992 book, The New Canada, Preston Manning traced western populism and its variants back to Louis Riel and Métis objections to land surveys in 1869, in response to decisions made in Ottawa with no regard for locals.

“This was the first of what was to be a continuous series of confrontations between the federal government and western Canadians,” writes Manning.

Riel’s execution, in 1885, interestingly, set off another variety of regional conflict in Canada, with Quebecers favouring leniency, rumours of an Indigenous uprising to free Riel and outrage in Manitoba. “He shall hang,” said Macdonald, “though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour.”

As Riel began the line “deliver us from evil” in the Lord’s Prayer, hooded, with a noose for a necklace, the trapdoor opened under his feet.

Macdonald’s Tories were wiped out in Quebec. And, Wilfrid Laurier, declaring “Had I been born on the banks of the Saskatchewan, I would myself have shouldered a musket to fight against the neglect of government and the shameless greed of speculators,” helped usher in the Quebec Liberal era.

For the next century, land and resources dominated the precarious relationship between Ottawa and the rest of Canada.

In 1883, farmers were reeling from frost and drought that had ravaged crops. At the time, the Canadian Pacific Railway was charging exorbitant rates to move goods from the prairies to international markets. Basically, because they had to ship by CPR, and the price of goods was determined internationally, the take-home earnings were depleted.

The farmers formed the Manitoba and Northwest Farmers’ Union, demanding control over their resources and reasonable freight rates. Going back to the late 19th century, people were mad about rules that made it nigh impossible to build or use competing rail lines.

- A brief explainer of the alienated West: where it comes from and how it will respond

- Western premiers warn of 'frustration and alienation' after election result sharpens regional divisions

- 'This isn’t just anger': Seven prominent voices assess the post-election mood out West

- Rex Murphy: Western anger was hot before the federal election. Now it's molten

While there is the grain and train side, there’s also the side of western alienation that’s rooted in how many seats the west has in Ottawa — again, debates that continue over things like an elected Senate.

Frank Oliver, publisher of Edmonton’s first newspaper, the Bulletin, compared in August 1885 the administration of the west as “despotism as absolute, or more so, than that which curses Russia.”

“The people of the North-West are allowed but a degree more control of their affairs than the serfs of Siberia.”

***

Even after they became provinces, Manitoba in 1870 and Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, none had control over their resources, including the oil and gas wells that were being drilled by the end of the 19th century. (British Columbia had more powers, comparatively.)

For the rest of the west, it took sending protest votes to Ottawa to change that. In part, you can thank immigrants for this — many of them from the United States and Britain, who, in the words of historian W.L. Morton, gave “western discontent a vocabulary of grievance” in a heady mix of “American populism and English radicalism.”

The National Progressive Party, created out of the agricultural reform movement, formed the second largest party in Parliament in 1921. By 1930, they’d successfully pushed for what’s called the Natural Resources Transfer Agreement. (Gibbins points out that this was essentially meaningless at the time since agriculture was crippled by the Depression and oil and gas hadn’t yet truly kicked off; nevertheless, it’s an important marker.)

“Because of this amendment, the royalties from oil and gas from Leduc and other petroleum reservoirs in Alberta flowed to the Alberta government in Edmonton rather than to the federal government in Ottawa,” writes Manning.

The people of the North-West are allowed but a degree more control of their affairs than the serfs of Siberia

Even then, the attitude the rest of the country served Ontario and Quebec hadn’t disappeared. C.D. Howe, the forever-glowering Liberal cabinet minister, told Alberta premier Ernest Manning in 1952 that the needs of eastern and central Canada needed to be met before gas exports to the U.S. were allowed.

If that was an exercise in saying the loud part quiet, in 1980, the Liberals under Pierre Trudeau said the quiet part loud, announcing the National Energy Program, which would create “”security of supply and ultimate independence from the world oil market.”

Mainly, it just infuriated Albertans, by a system of price controls, taxes and a degree of public ownership that were meant to stabilize and secure prices, but which cost Albertans tens of billions of dollars. (The Liberals, then as now, didn’t have any seats between Manitoba and the Rockies.)

By any metric, the early 1980s were the high-water mark for alienation and separatist sentiment in Alberta. In 1982, voters in Olds-Didsbury elected Gordon Kesler, an actual separatist, in the provincial election. Yet, the west — via premier Peter Lougheed, for example — had a significant impact on things such as constitutional negotiations.

“It looked a lot like it was written in Edmonton, or Regina,” says Gibbins.

Up until the mid-1970s, the west was in decline, in terms of economics and the population; with the petroleum industry, and changes to the international market more generally, Alberta was on the upswing, seen as a “new Canada,” Gibbins says.

“At the same time, the national government failed to reflect that,” Gibbins says. “Western alienation was the search for leverage, if you want, for leverage on the national political stage.”

Many westerners see a kid-glove treatment of Quebec that fuels alienation of all sorts.

Equalization payments, for example, first introduced in 1957, are widely seen in the west as a funnel of money to other provinces, particularly Quebec. Same for the 1986 decision to award the CF-18 maintenance contract to Canadair in Montreal, over the Winnipeg firm Bristol Aerospace.

The rise of Manning’s Reform party was in direct response to these pressures through the 1980s.

***

If it feels like history’s repeating itself, that’s because there is an eerie sense of déjà vu throughout.

Take the 1997 election, when Jean Chrétien’s Liberals did poorly across the west. Chrétien’s fix was to strike a committee, with 11 permanent members from the House of Commons and the Senate, and 27 others who rotated through. They visited 28 communities across the west and reported back in 2000.

On page six, the report explains the angst in the west over the National Energy Program, and suggests the government commit to not introducing a carbon tax.

Western alienation was the search for leverage

The carbon tax, of course, is one of the core grievances against the current federal government in Ottawa.

Even more amusingly, the task force reaches a conclusion that wouldn’t remotely shock any already alienated westerner: the system is good, westerners just aren’t aware of it, and the government should redouble its efforts to inform them.

Faron Ellis, a politics professor and pollster at Lethbridge College, pointed to Trudeau declaring en français that he would stand up to oil companies, a rehash in some ways of his earlier promise to “phase out” the oilsands.

“Alienation arises from people feeling ignored, in this case, Albertans feel they were attacked,” said Ellis.

***

From 1878 to 2019, there’s a long line of alienation running through the west. At some points, it’s included everything west of Kenora, Ont..

“It’s more concentrated this time in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and I think it’s also more intense, partly because of that concentration,” Manning says.

In the spring provincial election in Alberta, 13,531 people voted for the Alberta Independence Party, only a few thousand votes behind the provincial Liberals, but still less than one per cent of the vote. And, a former Mountie and conspiracy theorist, Peter Downing, has created Wexit Alberta (with a Saskatchewan arm, too) to attempt to create yet another separatist wing. That group was responsible for a major online pro-“Wexit” push in the aftermath of the campaign.

“So why is it suddenly seen to be explosive now? It’s being presented as an ‘us versus them,’” Thomas says. “What explains it the best is this idea that partisanship is being seen as social identity, which means you identify with Alberta as a group — and Alberta as a group is oil and gas and conservative.”

Alienation arises from people feeling ignored

All of which raises the question of what to do about it? Ellis — who describes himself as an alienated westerner — doesn’t see it as that bad.

“When I start to see people … putting their person, their face, their time, their name, behind a movement, a serious political movement, then I’ll say ‘yeah we’re back to 1980 levels,’” says Ellis.

In January 2001, several Alberta conservatives put pen to paper to explain what they felt ought to be done about Alberta’s place within confederation. The Alberta Agenda was signed by many prominent conservatives, including future prime minister Stephen Harper and a young guy named Ken Boessenkool, who had been an adviser to Canadian Alliance leader Stockwell Day.

“The sentiment that drove us to write the original Alberta Agenda is repeating itself,” Boessenkool told the Post.

That sentiment, as McGill professor Andrew Potter wrote in 2011, was “Jean Chrétien telling everyone who would listen that Albertans were untrustworthy.”

“When we wrote the Alberta Agenda, Ralph Klein was not a champion of the Alberta Agenda. He was unhappy when it came out and he said so publicly,” says Boessenkool. “I wouldn’t ever say Ralph didn’t have a pulse on Alberta, but Ralph certainly didn’t reflect in the same way that Jason Kenney and Scott Moe are reflecting the angst that I think is real.”

As Kenney told reporters recently, he believes he must “offer constructive alternatives” to Albertan angst, and described Albertans as patriots.

“I think the solution to frustration that’s expressing itself in separatist sentiment is positive ideas about reforming the federation for a fair deal for Alberta,” he says.

What the so-called firewall letter laid out was a proactive and positive path for steps Alberta could take to gain similar autonomy to Quebec and Ontario: there could be a provincial police force, instead of the RCMP patrolling far-flung areas of the province, or an Alberta Pension Plan, or Alberta could collect its own income tax and force Senate reform.

“We wanted to channel that angst into productive policy changes that Alberta could do unilaterally to make us similar to Quebec, similar to Ontario,” says Boessenkool.

Whatever happens next, Manning says he’s long argued that there’s a benefit to this raucous western populism.

“That bottom-up energy, which is hard to manufacture, if it can be channelled into answers to whatever’s causing the anger, it can be a very positive force for good, and I think that’s the challenge right now.”