The affordability of housing, the availability of public services, and the cost of climate change policies are all affected by immigrants.

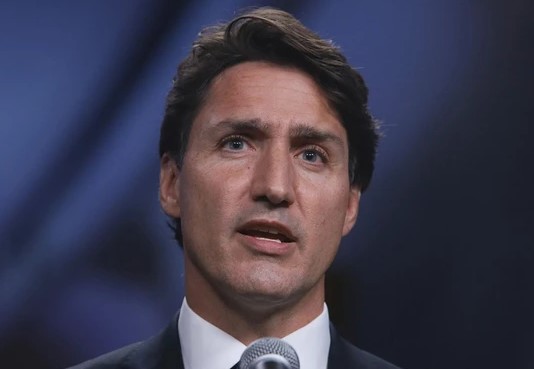

The Trudeau government is on record that it will increase the number of immigrants from 300,000 in 2018 to 411,000 in 2022. This increase will have serious implications for the three hottest-button issues of the 2021 election: the high cost of housing, the inadequate capacity of medical and other public facilities, and climate change. Yet in their campaign documents, none of the three major parties discusses the effects of immigration on these issues or promises to change existing immigration levels or policies. Canadians deserve better.

The effects of immigrants on the cost of housing are obvious. After arriving in Canada, people must live somewhere. They thus add to the demand for housing and, other things being equal, the excess of demand over supply. In recent years that excess demand has significantly raised the already high inflation-adjusted prices of single-family homes, condominiums, and apartments.

These high prices have motivated the major parties to promise policies to increase supply through the financial encouragement of construction or outright government ownership of rental facilities. Though such policies have been promised in the past the record shows that they have proved inadequate. Because the need for new construction is currently much larger than the ability of governments to finance it, current promises are likely to face the same fate.

Another set of policies promised by the three leading parties involves reductions in the demand for housing. The cheapest and most risk-free proposal sees the imposition of restrictions on the purchases of dwellings by foreigners. Many Canadians applaud this idea and foreigners have no political clout to oppose it. But even if the policy did stop foreign purchases, the effect on prices would be minimal because demand from foreigners makes up only a small proportion of the total. Moreover, to realize speculative or investment profits foreigners have to sell dwellings so that in effect they raise prices when they buy and lower them when they sell. And, of course, Liberal proposals to provide subsidies to new home-buyers will increase demand, possibly by more than restrictions on foreign ownership will reduce it.

The reality is that almost all demand for housing is caused by population growth, of which in recent years immigration has accounted for about 80 per cent. It is hardly rocket science that reducing the number of future immigrants would reduce demand and help bring it in line with supply.

Immigrants also add to the excess demand for medical services, whose existing supply cannot prevent both long waiting lists and sometimes acute shortages of both hospital beds and family physicians. Newcomers also cause excess demand for roads, public transit and recreation facilities, which results in traffic congestion, as well as overcrowding on buses and in public parks.

Those currently running for office promise to alleviate these problems with increased spending on health care and infrastructure. But such promises are likely to produce the same results as similar ones made in past elections. Some new facilities will be created but at best they will enable supply to keep up only with the natural increase in population, the rise in income, and the overall aging of the population — but not with the demand created by the much larger number of immigrants.

Immigrants also have an important influence on Canada’s efforts to prevent global warming through reductions of CO2 emissions. In 2016 our per capita output of such emissions was 15.09 metric tons. The 323,190 immigrants that year thus added 4.88 million metric tons to the country’s emissions and correspondingly raised the cost of measures needed to reach the emission targets Ottawa has announced. But two-thirds of these emissions would not have taken place if recent immigrants had remained in their (on average) low-emission home countries.

The negative effects immigrants have on the affordability of housing, the availability of public services, and the cost of climate change policies could be reduced by lowering immigration to 100,000 a year, a number I believe would allow ample numbers of skilled workers and refugees alike to meet both our labour market needs and our international humanitarian responsibilities. The proposed number can readily be raised or lowered if evidence suggests that demand or cyclical economic conditions warrant it or supplies of housing and public facilities have caught up with demand.

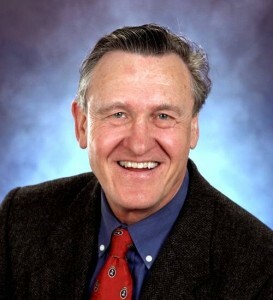

Herbert Grubel, former parliamentary finance critic for the Reform Party of Canada, is professor emeritus of economics at Simon Fraser University.