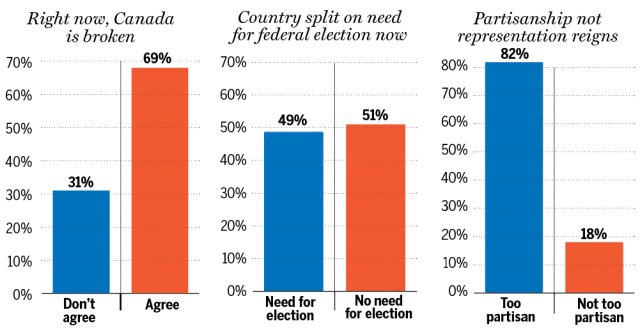

If 69 per cent of Canadians think the country is “broken,” as a DART & Maru/Blue poll conducted for the National Post suggests, that means it’s not just one kind of Canadian: not just Albertans furious about their landlocked bitumen; not just Quebec nationalists who feel Canada cannot accommodate their perfect society; not just those who think it absurd that a provincial pipeline dispute in northwestern British Columbia could shut down the Canadian National Railway almost four provinces away for two weeks.

It’s a supermajority. The finding is alarming on its face.

The reaction among media and academic types, however, has largely involved the rolling of eyes. Some, like Scott Gilmore at Maclean’s, noted how well Canada fares in various international indices measuring quality of life, democracy, and freedom of all flavours. “We can do so much better,” he conceded, but he advised appreciating that “what we already have is pretty damn good.”

Other nations’ deficiencies say nothing of our own

Many others, including progressive voices, evinced what can only be described as an affronted patriotism. Twitter teemed with helpful links demonstrating what happens in truly broken countries — mostly the United States, naturally, and mostly involving medical bills.

It’s a bit odd. The crimson library of domestic and international commentary circa 2015-2016 congratulating Canada for electing Western democracy’s last great hope in Justin Trudeau, and for being so tremendous in general — everything Donald Trump’s America is not! — should haunt its authors like an arrest warrant. But at the time, it did produce some very healthy and appropriate (if at times also hyperbolic) backlash commentary.

“Better than our dysfunctional neighbour” isn’t a standard anyone would accept from their family members, those commentators noted. Canada has world-class problems that should make us all wince, they properly observed — none more critical than the mostly shrinking but still massive socioeconomic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and the horrifying outcomes to which those indicators lead in some communities: staggering rates of suicide, homicide and other violent victimization.

No other country has anything to do with any of that. Other nations’ deficiencies say nothing of our own. Yet it’s clear throughout recent history — perhaps most plainly on health care — that America’s perceived failings in particular have been a convenient excuse for self-styled progressive Canadian governments not to aim higher, better and faster.

It was the perfect time to take stock of that phenomenon. And the statement “Canada is broken” would not have been out of place in many of those reality-check pieces. So why is it being received so poorly today?

Canadian news consumers are used to some pretty inflammatory rhetoric about this country, after all. Anti-monarchist obsessives and proportional representation fetishists routinely allege that we are literally not a democracy. Michael Wernick, then Canada’s senior civil servant, sat down in front of a committee investigating the SNC-Lavalin affair and warned of violence and assassinations to come, and this was warmly received in the establishment salons. Our prime minister not so long ago admitted participating in an ongoing genocide, and hardly anyone even noticed. Crucial Canadian institutions, from the House of Commons and Senate to the justice system, are routinely and accurately described as broken.

And never mind “broken.” In his recent book Democracy in Canada: The Disintegration of Our Institutions, renowned and decidedly non-radical University of Moncton political scientist Donald Savoie argues Canada was terribly designed to begin with: the square pegs of Britain’s unitary state jammed awkwardly into the round holes of a bilingual federation, which have withered and atrophied in place even as the country has transformed enormously around them.

The House of Commons, the Senate, the Cabinet, the media and the public service are all shadows of their former selves, Savoie argues. “Canada’s national institutions lack the capacity to articulate and incorporate Canada’s regional perspectives in shaping Ottawa’s policy and decision-making processes,” he writes. “Canada is doing poorly when it comes to regional equality when compared with other federations.”

“Canada is not broken,” he told the Post’s Stuart Thomson. “Canada’s institutions are broken.”

America’s perceived failings have been a convenient excuse for self-styled progressive Canadian governments not to aim higher, better and faster

To the extent there’s a distinction to be found there, it’s not clear which is worse. The annual Edelman Trust Barometer survey shows highly educated and otherwise highly advantaged Canadians trust their institutions — the government, media, business, NGOs — far more than the general population. It’s not a situation to be taken lightly.

Not every regional grievance is valid, of course, but regional grievance is precisely the spirit that animates Michelle Rempel Garner & Co.’s Buffalo Declaration: “Many of the people who we represent have expressed to us that they feel (the) Canadian federation is deeply broken, and inherently unjust,” it reads. “Canada is broken” sentiment rises to 83 per cent in Alberta, according to the DART & Maru/Blue poll. You can’t sneer and scoff that away, and no one should dare try.

The Fathers of Confederation might well find consensus on the word “broken” to describe Canada, 153 years on. It means “not functioning as intended,” not “this might as well be Venezuela.” Surely 26 million Canadians can’t be wrong.

• Email: cselley@nationalpost.com | Twitter: cselley