Impatience lives on François Legault’s face, often in competition with exasperation, incredulity and scorn. His lips pucker and his eyes squint. His body seems to itch inside his suit. Watching Legault, the leader of the Coalition Avenir Québec party and possibly the next premier of Quebec, is to observe a man constantly in a fit of pique, with only social convention holding him back.

In a way, his impatience is understandable. For the last seven years, Legault, 61, has sought to lead Quebec by way of a party that is neither Liberal nor Parti Québécois—a feat last accomplished by the Union Nationale party in 1966, when Legault was nine years old.

And much like the Union Nationale of yore, the CAQ brands itself resolutely conservative, with emphasis on entrepreneurship, private investment, natural resource development and an end to wanton government interventionism.

Suffice to say, the last five decades in this province haven’t been kind to Legault’s stated brand of conservatism. Though conservative, that Union Nationale government oversaw the burgeoning of the Quebec state. It created five government ministries, a network of universities and another of finishing schools, a state-funded radio station and the province’s system of publicly funded healthcare.

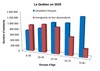

The Quiet Revolution, which began under Union Nationale Premier Daniel Johnson’s reign, birthed the Quebec Model, in which the provincial government became the vehicle of choice through which Francophones disabused themselves of the Catholic Church and the English ruling class. It grew exponentially as a result. Between 1989 and 2009 alone, public spending in social services in Quebec grew by 60 per cent, compared to 29 per cent in Canada as a whole, according to a 2013 Haute Études Commerciales study.

The CAQ ostensibly wants to reverse all of this. “The ‘Quebec model’ is as heavy as it is underperforming,” read the CAQ’s inaugural platform of 2012. Even then, Legault was impatient. “Enough already, it’s time for change!” was the party’s slogan that year.

Six years and two elections later, the CAQ and the Liberal Party, which has held power for all but 18 months of the last 15 years, are in a virtual tie in the polls. Legault’s likelihood of victory on Oct. 1 lies in his party’s ability to harvest the collective goodwill of Quebec’s Francophones outside Montreal and its immediate suburbs. Until the advent of the CAQ, this great swath of territory was, with a few exceptions, relatively fertile ground for the separatist Parti Québécois.

By essentially usurping the PQ’s nationalist vote — in part, oddly enough, by renouncing sovereignty outright — the CAQ has birthed a precedent: for the first time in nearly half a century, sovereignty isn’t a defining issue of a Quebec election campaign. In fact, it’s hardly been mentioned at all.

This is all the more impressive considering that Legault himself is a former Parti Québécois minister who spent much of his early political career pushing the economic necessity of extricating Quebec from Canada. His change of heart on the subject, which mirrors those of many nationalist Quebecers, is one of the main reasons why he may become premier after Monday’s election.

Yet Legault’s many critics say he has simply swapped the knotty identity issue of sovereignty for an even knottier one: the roughly 50,000 immigrants arriving in Quebec every year. Legault has spent much of the campaign talking about new arrivals to Quebec and their allegedly nefarious effect on French language and culture. A CAQ government, he has said, would deport any immigrant who didn’t pass language and values tests after three years.

To others, it appears Legault has renounced his conservative principles out of political expediency to please Quebec’s vast, centre-left voting constituency. “François Legault is very, very comfortable with the Quebec model of high taxes and government intervention,” says Joanne Marcotte, a veteran advocate for fiscal conservatism in the province.

Having come into existence less than ten years ago, the Coalition Avenir Québec now has a sense of permanence to it — and at the very least the potential to replace the Parti Québécois as the definitive nationalist voice in Quebec. The question is, if Quebecers vote for Legault and his party on Monday, what exactly are they voting for?

The Coalition Avenir Québec began life in 2011 as a thinly veiled think tank, its ultimate goal to birth a conservative party to counter the Liberals on the economy and the Parti Québécois on the national question.

Legault, who declined interview requests for this article, co-founded the think tank and assumed leadership when it became a political entity. He pitched himself to voters as a former politician — he left the PQ in 2009 — reluctantly compelled back to the scene if only to right Quebec’s political morass. “Neither I nor my wife want to spend 10 years in politics, but I feel a certain responsibility in Quebec to leave something to my kids, a prosperous Quebec, and right now that’s not what I see,” he told me in 2011 for an article in Maclean’s.

The ensuing political party, officially registered on Valentine’s Day in 2012, was made up of disaffected sovereignists and disaffected federalists in rough equal measure. Political operatives from the defunct conservative party Action Démocratique du Québec, the CAQ’s ideological predecessor, rounded out the brain trust. In the 2012, the CAQ elected 19 MNAs, including Legault and six former ADQ MNAs. Three former PQ MNAs also defected to the CAQ..

The party’s early inclinations reflected Legault’s centre-right pensées. He’d entered politics in 1998 after a successful career as an entrepreneur; he co-founded the Air Transat discount airline in 1987, netting him the business bona fides for a successful political career.

In Toward A Successful Quebec, Legault’s 2013 slogan-heavy book, he decried how successive Quebec governments doled out tax credits in the name of innovation without much oversight or record of success. A CAQ government would eliminate these, along with school boards, he pledged at the time. It would allow for private health care options and cut Quebec’s civil service down to size. “There were a lot of audacious ideas in the early days of the party,” says economist Robert Gagné of the HEC.

He also swore off sovereignty, saying a CAQ government would never hold another referendum on Quebec’s future within Canada.

This was a marked departure from Legault’s own thinking just three years before. In 2009, as the Parti Québécois finance critic, he wrote a “Year One” budget for a sovereign Quebec. “The province’s provincial government is practically condemned to powerlessness,” he wrote. In 2015 the CAQ changed its constitution to call for “the development and prosperity of the Quebec nation inside Canada.”

Many nationalist Quebecers follow Legault’s evolution on the subject. Support for the Parti Québécois, whose raîson d’être is to usher in Quebec sovereignty, has with one exception declined in every election since 1998. Meanwhile, young people haven’t replaced the movement’s aging Baby Boomers. According to a recent IPSOS poll, 19 per cent of voters between 18 and 25 say they are sovereigntists, while the issue itself is dead last in a list of priorities.

Though he doesn’t count himself as a CAQ supporter, long time sovereigntist and former Bloc Québécois MP Jean Dorion understands the public’s fatigue with the subject. “The whole constitutional issue is anxiety-inducing,” he says. “When there’s a referendum, people are summoned to pronounce themselves ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on something they don’t really quite understand. If and when someone like Legault shows up and says ‘I’m not talking about that anymore,’ it’s a relief.”

Among the relieved is Benoit Charette. Elected in the riding of Montreal exurb of Deux-Montagnes under the PQ banner in 2008, the 42-year-old Charest defected to the CAQ in 2011. “Sovereignty was the reason I left the PQ,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll see another referendum in my lifetime. Quebec’s future is in Canada.”

Yet Legault’s many critics, Dorion included, say he has adopted immigration as a proxy issue for sovereignty. For decades, nationalists blamed the supposed retreat of the French language within Quebec’s borders on the province’s historical Anglophone community. Legault has instead taken to blaming immigrants, whom he said weren’t adopting French in their daily lives. Though novel, there doesn’t seem to be much truth to the notion. A 2017 study by the Office québécois de la langue française said use of French in the workplace actually increased amongst Anglophones and allophones (those whose first language is neither French nor English).

If we start saying that immigrants can’t have too dark skin or be too religious and must speak perfect French we’ll end up with no one

Still, Legault has persisted. “There’s a risk that our grandkids won’t speak French,” Legault said while campaigning through the Laurentides town of Saint-Colonban, which is 96 per cent French. (“It’s like he forgot about Bill 101,” quipped demographer Frédéric Castel, referencing the Quebec law that compels the children of immigrants to go to French school.)

If elected, Legault promises to reduce by 20 per cent the number of immigrants Quebec takes in, to 40,000 a year. In 2016, Legault said a CAQ government would institute a values test for immigrants after spending three years in Quebec, with expulsion for those who failed.

That same year, the party published an ad featuring a woman in a chador, the body-covering Muslim garb, alongside pictures of Liberal Premier Philippe Couillard and PQ leader Jean-François Lisée. “Couillard and Lisée favour the chador for teachers in our schools,” it read. (The party’s reasoning, which might charitably be called tangential, was that both Couillard and Lisée favoured bans on face-covering garb in schools, but not body coverings.)

Though Quebec selects the majority of its economic immigrants, only the federal government has the ability to remove people — and then, only on grounds of serious criminality or misrepresentation. In a recent conversation, a senior source at Immigration and Citizenship Canada scoffed at Legault’s deportation platform. “If you were to say, ‘Well, you didn’t pass the language test, therefore you need to leave Quebec,’ we can’t enforce that. There is no mechanism to do that,” the source said.

Moreover, given Quebec’s manpower shortage, it is a particularly inopportune time to reduce immigration levels. Between 1981 and 2010 the province lost 5.1 per cent of its population aged between 15 and 44 years; in Ontario, that segment of the population increased by 26 per cent, according to a study by the Montreal Economic Institute.

“It’s an anti-market, anti-economy way of speaking. It’s bizarre,” says HEC’s Gagné of Legault’s plan to decrease immigration. “Picking immigrants isn’t like buying tomatoes. Demographically, we don’t have the luxury of cherry-picking. If we start saying that immigrants can’t have too dark skin or be too religious and must speak perfect French we’ll end up with no one.”

Faced with criticism, Legault has since backed off his contention that anyone will be deported. In the end, though, his immigration gambit might all be for naught. Though the issue occupied much of the media attention during the campaign — it was the most talked-about subject of the campaign, according to Influence Communication, a media monitoring company — a La Presse poll published this week said voter priorities focused on environment, health care, economy and education.

Immigration was a distant fifth, with less than eight per cent of voters believing it to be an important issue — a contention echoed by CAQ MNA Benoit Charette. “I honestly didn’t hear about the issue in my riding,” Charette says, adding his party’s preoccupation with immigration was “a communications mistake.”

Joanne Marcotte believes Legault’s impatience for power has pulled the CAQ so far to the centre that the party is no longer conservative. She doesn’t particularly blame him; as one of the province’s few rock-ribbed fiscal conservatives, Marcotte is all too aware of how lonely a perch it can be on the right in Quebec.

Still, she keeps a list of his decidedly un-conservative flip flops. During the campaign, Legault pledged to reinstate a flat-rate daycare fee for all parents, regardless of income — a policy axed by the Liberals in 2016 in order to help balance the budget, netting the government an extra $300 million per year. Legault has also stayed away from tax cuts, instead promoting an increase in family allowances. And though it promoted the idea in 2012, the CAQ no longer advocates for further privatization of the health-care system. Like the Union Nationale of 1966, the CAQ started on the right and promptly drifted leftward. “He’s a radical centrist,” Marcotte says. She means it as an insult.

Still, she’s voting for him, if only to be rid of the Liberals. “It’s unhealthy to keep voting in one government over and over for too long,” she says. “I’ll vote for Legault. He isn’t a conservative, but he’s the least bad of the bunch.”