The corner house on the quiet street looks well cared for. There are yellow flowers in the garden, canoe paddles leaning against the back door, a child’s bicycle in the front yard and a barbecue on the porch. Inside, the sound of happy voices, chattering away, some late-afternoon merriment interrupted by my knock at the screen door.

A little girl answers, and calls for her father. Peter Greyson appears, stepping from the home’s shadowed interior into the daylight. He is a slight man, 54 years old, soft-spoken and almost painfully polite. He apologizes for not returning my phone calls and speaks to me, amiably, about his life in Haileybury, a sleepy Northern Ontario town on the shores of Lake Temiskaming. He tells me that he is a single father, and that he still paints. But mostly, he says, he has been busy raising his eight-year-old twins.

“I haven’t really been in the headspace to think about the past very much,” Mr. Greyson says, shrugging in the direction of his daughters. “It was a long time ago. People around here know what I did — but no one ever asks me about it.”

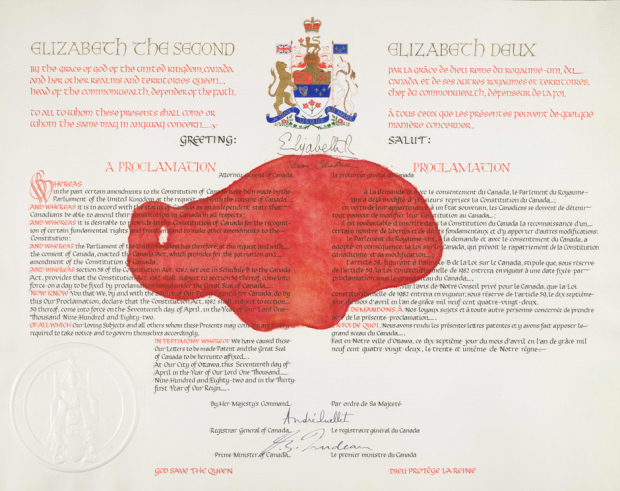

Even if they did ask it is unclear what, exactly, Peter Greyson might say, since all he is willing to say to me about July 22, 1983, the day 30 years ago he dumped red paint on the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982 — a vital Canadian historical document, signed by Queen Elizabeth II and then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau, that repatriated the Constitution and formally acknowledged Canadian sovereignty — is this: “I have no comment.”

But James M. Whalen of Fredericton, N.B., does have comment. In fact, it is a day, a story, he thinks about often, a cascade of events that, for years afterward, left him with nightmares. Mr. Whalen, a retired archivist, was working at the Library and Archives Canada building at 395 Wellington St. in Ottawa when Peter Greyson showed up.

Mr. Greyson was 24, an art student from Toronto. He was polite. He was well-dressed.

“He said he wanted to study the artistic design and calligraphy of the proclamation,” Mr. Whalen recalls, from his Maritimes home. “I retrieved it from the storage vault and laid it on a flat surface. No sooner had I laid it out than he whipped out a glue bottle — he had an Elmer’s safety glue bottle in his suit pocket — and poured red paint all over the document.

Library and Archives Canada

Library and Archives CanadaThe red stain covers some of the signatures on the document but they can still be read.

“I was stunned. Our job as archivists was to preserve and protect documents. I was flabbergasted. I grabbed his arm and he didn’t resist. I asked him why he did it and he said he was protesting American cruise missile testing over Canadian airspace.

“But I couldn’t see the connection between what he was saying and what he did. The logic seemed off to me.”

His aim, however, was dead on. Smoke, spilled drinks, crumbs, a leaky roof, mould and moth damage, these were among the worst-case scenarios for an archivist. But the willful destruction of an essential part of Canadian history, by a Canadian, had never happened before.

The proclamation, one of two existing copies — the other original was damaged by rain the day it was signed — was a big red mess. Geoffrey Morrow, the Archives’ senior conservator, raced to the scene from a basement laboratory. Using a small vacuum with a fine nozzle he sucked away the excess paint. What remained was a sizable red splotch. Meanwhile, shock waves reverberated through the archival world.

“We had this idea that there might be a conspiracy, that there might be people all over destroying prestigious documents,” Mr. Whalen says. “We didn’t know if [Greyson] was acting alone.” (A second bottle of Elmer’s glue filled with blue paint was discovered in his briefcase.)

Precious items were locked down. Procedures for viewing them altered. The Archives purchased a glass viewing case. The most significant parchments would henceforward be viewed by the public, if at all, only under strict supervision and only under glass.

But what to do about that red spot?

There was talk of cutting it out and transplanting in a fresh piece of paper. Chemical solvents were considered. Even laser removal surgery discussed. In the end a decision was made to do nothing.

“To cut a piece out of it would have altered the document,” Mr. Whalen says. “It would no longer have been authentic. And the other unique thing about it was that the Queen signed two copies, which was highly unusual. The one that she signed outdoors, it was raining, and somebody picked it up and accidentally rubbed it on their clothes and it got smeared, a bit.

“And the other one had paint thrown on it. So in my world we refer to them as the rained and the stained.”

Keith Minchin for National Post

Keith Minchin for National PostRetired archivist James Whelan with some memorabilia from the event: “We had this idea that there might be a conspiracy, that there might be people all over destroying prestigious documents.”

The stained (and the rained) currently reside in a state-of-the-art, climate-controlled vault in Gatineau, Que. The temperature is 18 degrees Celsius, the relative humidity constant at 40%.

“The document has held up fine,” says Catherine Craig-Bullen, manager of conservation treatment at Library and Archives Canada. “There is still a big red splotch on it, and it covers some of the signatures on the document, but you can read the signatures through the stain.

“We do bring it out on occasion for special tours. But you, Joe Public, if you wanted to see it — the odds are — no, you won’t.”

The document is now framed, and even when it is removed from the vault, on those rare occasions, it is often kept in a locked display case.

“[Greyson] defaced a national document, and it is tragic,” Ms. Craig-Bullen says. “But it is also interesting because the paint is so much a part of its history that when people request to see the proclamation they quite often request to see the paint-stained copy.”

Peter Greyson pleaded guilty to willfully damaging public property in October, 1984. He faced a maximum penalty of 14 years. Ottawa Judge David McWilliam sentenced him to 89 days in jail, to be served on weekends, plus two years probation and 100 hours of community service. Judge McWilliam noted that Mr. Greyson was an excellent student with no previous criminal record and quite possibly “a brilliant artistic future.”

Mr. Greyson never expressed remorse for his actions. He served his sentence, graduated, got a job in advertising, represented some Toronto artists as an agent and lived a low-key life before moving to Haileybury about 10 years ago.

His most recent job, which he resigned from several months ago, was as curator of the Temiskaming Art Gallery, a facility built, in part, with federal funds. Walter Pape, a local artist, sits on the gallery’s Board of Directors that hired Mr. Greyson in September, 2010.

“I never asked him about his past and I only heard about it after we hired him from people on the Internet,” Mr. Pape says. “It was never an issue. He was hired and he did a good job, and you can’t hang something like this over a person’s head for the rest of their lives.

“He was young and he did something stupid, I guess.”

James Whalen is less forgiving: “Somebody told me he was in charge of a gallery, and I thought he should be in charge of a paint store,” he snorts.

Mr. Greyson never did make it big, at least not in the art world, at least not yet. He paints landscapes of the local area, which, once upon a time, played muse to the Group of Seven. But he does not sell his work.

Toward the end of our conversation on the porch he sketches a Peter Greyson original in my reporter’s notepad — hand drawn directions to a nearby hiking trail where, he says, photographer Tyler Anderson and I could stretch our legs after a long drive.

“You guys should have brought a canoe,” he says.

Polite to the end, he takes my phone number, email address and promises to call — if he changes his mind about talking, if he decides to answer the question left hanging in the air: does he regret what he did, all those years ago?

I am still waiting for an answer. I imagine I am not the only Canadian who is.

National Post

A blot on Canadian history: First the Queen signed our Constitution, then an activist threw paint on it

Joe O’Connor

Laissez un commentaire Votre adresse courriel ne sera pas publiée.

Veuillez vous connecter afin de laisser un commentaire.

Aucun commentaire trouvé